American photographer, painter, sculptor, filmmaker, writer and activist- David Wojnarowicz (1954-1992) created a body of works that encapsulated New York in the 1980s, a time marked by culture wars and the AIDs epidemic.

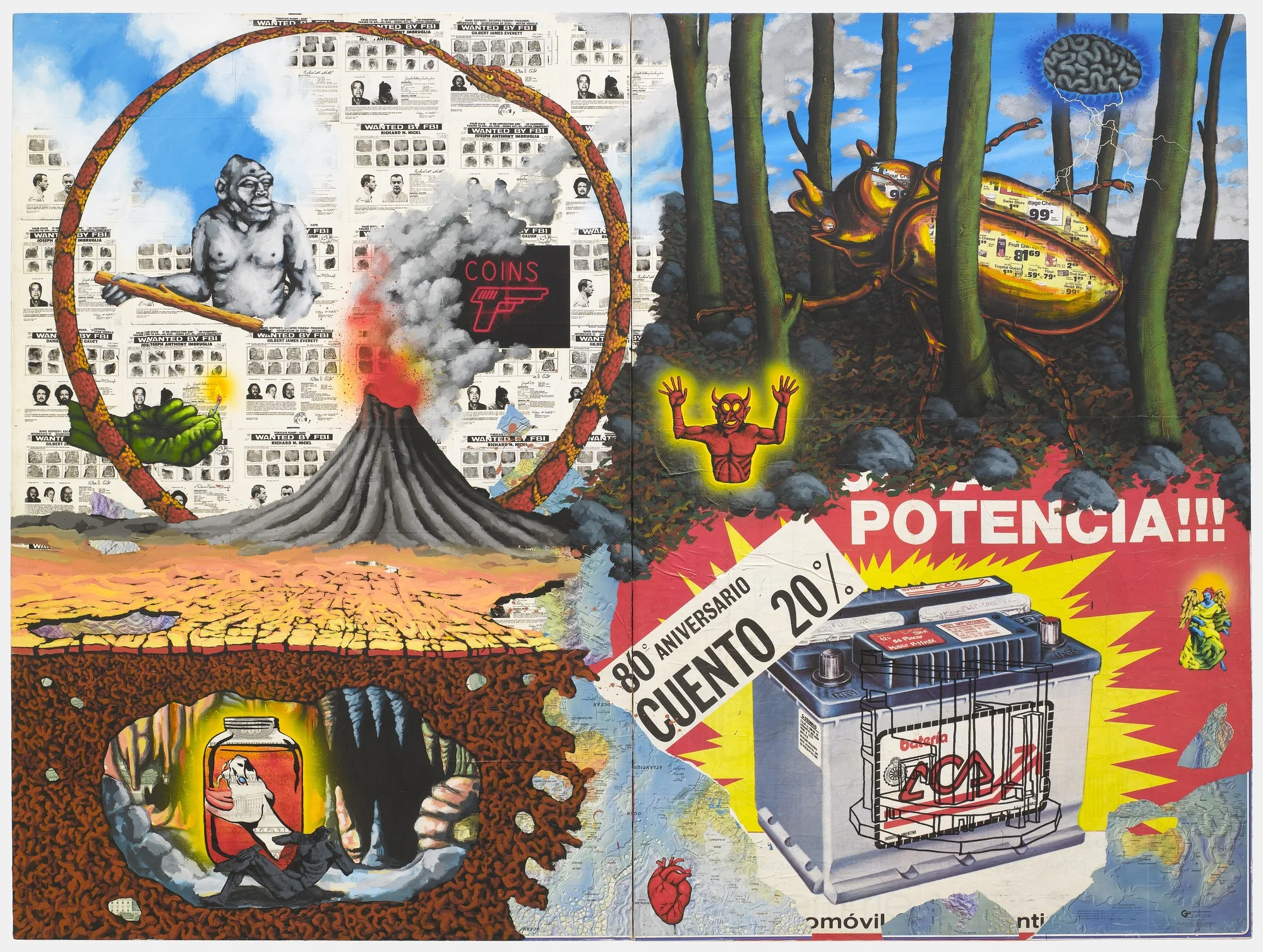

Fire, 1987. Acrylic and pasted paper on wood, two panels, 72 x 96 inches.

Hear from the artist directly in this interview by writer Matthew Rose, originally printed in Arts Magazine in 1988 and later republished in Art in America. Matthew walked into Gracie Mansion Gallery in the East Village where he first saw David’s work casually propped on the floor against a wall. Thinking they weren’t selling but immediately captivated by the synthesis of advertising with text and images, Matthew inquired about contacting the artist to do an interview. Excerpts from this powerful interview are below.

Untitled (Buffalo), 1988-89. Gelatin silver print, 16 x 20 inches.

On production:

MR: Does it take you a long time to finish a painting?

DW: I do a large painting over a period of time and I'm usually working on many things at once. I started this last show with notebook ideas, images, basic concepts of things. I used to paint directly-- whatever came into my head. When I started the work with the four elements--Air, Earth, Fire, Water-- the first images that occurred to me I knocked down, whether it was in words or drawings. I tried to push toward their references, their hidden meanings.

MR: Give me an example.

DW: With Fire, I would write out a series of ideas and associations relating to fire. Fire could be everything from the elemental fire to heat, anger, weaponry or impulses. With lists of these associations, I'd come up with thirty images, then I'd pull out maybeseven.

MR: What do you find when you finish a series of paintings?

DW: It's more what I find in the process. Understanding more about the source of my images, why they occur, their relation to my childhood. I'll look at things in a natural environment and small things like ants. In Earth, there are ants, timelessly pushing the earth around. I began to think about tractors, which do the samething…

History Keeps Me Awake at Night (for Rilo Chmielorz), 1986.

On the art world:

MR: What is the art world for you?

DW: Well, I haven't ever felt the art world is really about art, but about things that look like art…People love to pick up what they recognize already or what's been recognized for them as art. That's why you have these flurries of groups rushing off to find the next new style. It's never really anything about the art itself but what's turned up at the moment, so it must be art.

MR: But at the same time, you're willing to go about pursuing your own ideas and submit them to a society that doesn't understand what your paintings are about, or perhaps doesn't really care.

DW: I agree with you, but I think there are people who do, although they're hard to find. And there are people who use their own judgment and their own honest reactions to what they're looking at and attempt to deal with the work…the whole process is sort of a joke and at the same time, it's not.

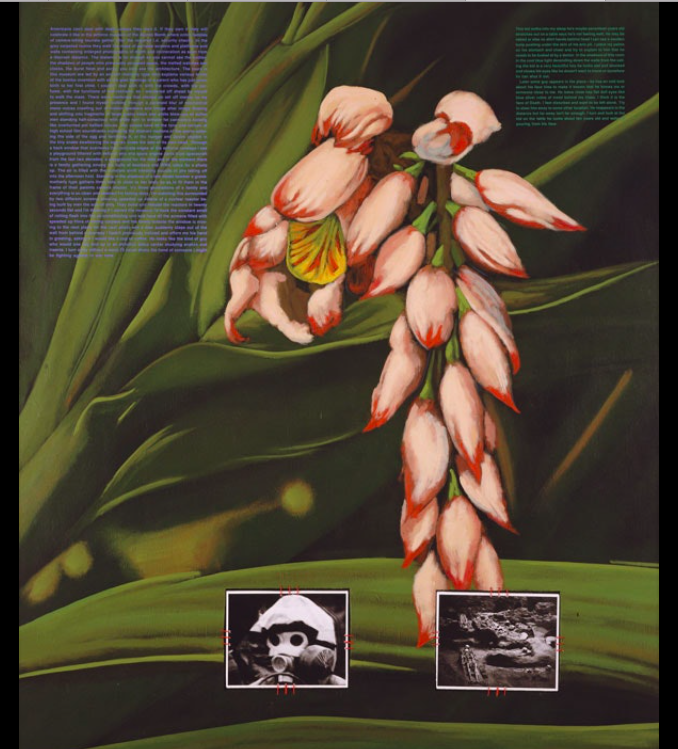

Americans Can’t Deal with Death, 1990. Two gelatin silver prints, acrylic, string, and screenprint on composition board, 60 x 48 inches.

On life:

MR: You mentioned you lived with ex-convicts.

DW: When I came off the street I lived with several ex-convicts in a halfway house for about two years. I had run into someone in Times Square who took me in to his room in a hotel there. At some point he wanted to get rid of me because I was turning his house into a menagerie, shoplifting animals from pet shops.

MR: You slept in doorways?

DW: I slept in doorways in Times Square. I managed to find my way--a place to sleep, something to eat. I was taken care of by different people. I found a job at this halfway house and met people coming out of prison--people who went around passing bad checks, stealing left and right. One guy who got me into the halfway house presented himself as a psychologist; he was a fake. But once in, I had a certain amount of structure where I could kind of repair the damage and get off the streets, find work, live a regulated lifestyle for a couple of years. And it worked, because one thing I discovered living on the streets is that you can't change it. People yell, "Get a job," but you can't get out of it; you carry a certain amount of energy that no matter how good your clothes are, you're surrounded by this energy and people pick up on it right away. They see it in your eyes. It took me close to a year when I finally got off the streets to find some janitorial job in a warehouse.

You can read the entire article here. Matthew is an artist and writer living in Paris who regularly contributes to The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, Artblog and Modern Painters. Check out Matthew’s artwork on Instagram.

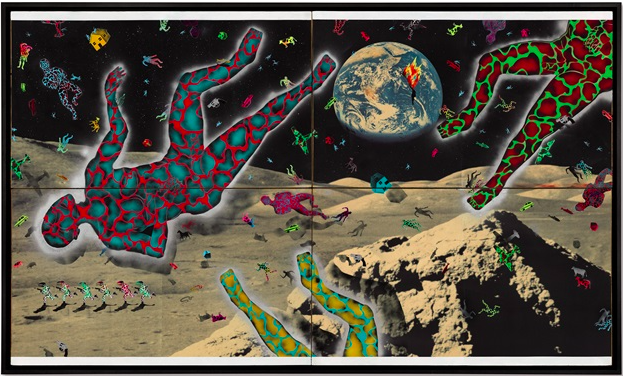

Science Lesson, 1982-1983. Acrylic, spray enamel and photographs mounted on four Masonite panels, 96 x 144 inches.

Today, David’s estate is controlled by P.P.O.W. Gallery in New York. Although finding his works can be challenging, if you can, he’s worth the investment. A 1982-83 collage painting sold for $708, 500 (estimate at $400k-$600k) at Christie’s Post-War Contemporary Art Evening sale in New York on May 17, 2018.

One of David’s most iconic works, the film titled A Fire in My Belly, can be seen below.